Posters

-

Via Library of Congress, Yanker Poster Collection, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016648550/. ↩︎

-

Susan Saxe has a sparse Wikipedia entry. She was Nancy Gertner’s first case, which the latter writes about in In Defense of Women: Memoirs of an Unrepentant Advocate Beacon Press, 2011), chap. 1 (sample with salient details). ↩︎

-

Lucinda Franks, “Return of the Fugitive,” The New Yorker, June 5, 1994, https://archive.ph/5mJ5P. ↩︎

-

See a related poster for American men on this blog, one of them Black, captioned “Bonds and justice will smash the Nazis. Not bondage!" ↩︎

- “Beware the cancer quack / A reputable physician does not promise a cure, demand advance payment, advertise” by Max Plattner, Works Progress Administration – Federal Art Project NYC, for the U.S. Public Health Service in cooperation with the American Society for the Control of Cancer, ca. 1936–38, via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518641/.

- “No home remedy or quack doctor ever cured syphilis or gonorrhea / See your doctor or local health office” by Leonard Karsakov for the United States Public Health Service, ca. 1941, via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/96502760/.

-

“Trusted with kids, not with a vote…” (DC Vote, 2006), Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010650572/; “Both will save your life. Only one has a vote in Congress…” (DC Vote, 2006), https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010650571/. ↩︎

-

Ike Allen, “A History of Congress Messing With DC: 50 years of home rule—and federal meddling," Washingtonian, November 8, 2023. ↩︎

-

President Biden will allow Congress to overturn new D.C. crime law, NPR, March 2, 2023. ↩︎

- "Protect your hands! You work with them," poster (silkscreen) by Robert Muchley for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518513/.

- "Be careful near machinery," poster (woodblock) by Robert Lachenmann for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, ca. 1936–1940. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518717/.

- "Work with care," poster (woodcut) by Robert Muchley for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936 or 1937. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92517365/.

- "Failure here may mean death below – safety first," poster (woodcut) by Allan Nase for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936 or 1937. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518429/.

- "Backyards, Baltimore, Maryland," black and white photograph by Dick Sheldon for the Farm Security Administration, July 1938. Repository: The New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ba309cea-94b2-4288-e040-e00a18066c61

- “Get away from the window! Curiosity is death!” The sketch shows a terror- or awe-stricken family looking out, many mouths wide open. Instead of gawking, the poster commands readers, “Stand individually behind pillars!”

- “Never remain standing on an exposed road!” “Always seek cover!”

- “Don’t stand behind the door!” This is followed by more advice about strong pillars or load-bearing sections of the wall.

- “Panic is worse than an air raid!” Pictured are people hurrying down the stairs, one person holding a candle, another an oil lamp. Underfoot is a small child who has fallen down, and ahead of these residents is an old man with a cane, about to be trampled. Instead of panicking, the readers are told, “Don’t worry about an attack at night!” Pictured is a man under a duvet sleeping soundly.

- “Never stand in the middle of the room!” The picture below this final warning shows a domestic space in which a man in bare feet and a nightshirt has behaved correctly: He is standing in a corner, an empty bed nearby, but the middle of his floor has disappeared.

- Puck cartoon marking the new year in 1914. A young man (the New Year) in a smoking jacket and a vest labeled 1914 says to the old year, dressed as Uncle Sam, "Have something on me, old man! Whatll it be?" The choices are two whiskeys, one marked "hope" and the other "fear". They are in a well-furnished upper middle class salon with an overhead electric lamp lighting their faces. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011649657.

- Cartoon sketch by John T. McCutcheon titled "Is that the best he can wish us?," published in the Chicago Tribune on December 31, 1917. It portrays an old man, 1917, disappearing into the annals of history (literally pages, one marked "history") as he wishes a younger man with a globe for a head ("The World"), "Scrappy New Year!" The new year is dressed as a soldier and is weighed down by infantry kit as well as a few artillery tubes and merchant ships. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010717171/.

- Red, white, and blue New Year’s poster with Baby 1919 flanked by Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty. Behind them is a big red sun with the text, “World Peace with Liberty and Prosperity 1919.” Europe was still in turmoil and experiencing violence, but Americans had reason to be optimistic. Thus, this lithograph from United Cigars (logo at Liberty’s feet) seems apropos for the time. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652819/.

YWCA War Work Council poster, ca. 1917 (United States)

Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002707403

Poster from an Antiwar, Lesbian, Feminist Fugitive, ca. 1970

Poster with a message by Susan Saxe, depicted in the drawing.1 Based on the text, the poster is probably from around 1970, when its author, a Brandeis senior and antiwar activist, went on the lam after robbing a bank and a National Guard Armory. On the FBI’s most wanted list, she was captured in 1975 and did seven years in prison.2 Her roommate, Katherine Ann Power, surrendered in 1980.3

A New Era for Women Workers, Minority Women and Lesbians. 1976 poster by a Seattle organization called Radical Women.

Via Library of Congress, Yanker Poster Collection, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016649885/.

This Italian fascist poster prefigures the disgusting rhetoric of Putin and Trump: “On them rests the blame!” by Gino Boccasile, ca. 1942–45.

Via David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, https://idn.duke.edu/ark:/87924/r4bp0064p.

“Stamp ‘em out! Buy U.S. stamps and bonds.” Poster by Thomas A. Byrne. WPA War Services of La., circa 1941–43.

Via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518290/.

World War Two Poster Marking the Dignity and Humanity of Black Women on the Home Front

The American Front for Victory – This poster from World War Two operates on two levels. First, it emphasizes the contribution of “The American Front” to the victory for which the nation was fighting. American front because this was about the home front, the people, many of them women, contributing to victory in industry, in agriculture, through service, and with their savings. Second, the name makes an important statement about the women it pictures working. They are Black. In large parts of the country, racist Americans cast the fitness of Black people as American citizens in doubt, to say nothing of questioning their very humanity.1 Here, by contrast, four Black women are depicted doing dignified work for the national cause.

Moving clockwise from the top, one woman, wearing some kind of civilian uniform, is holding a bucket marked “save” and is participating in either the sale or purchase of “Defense Bonds”; another is working a potato field with the words “strong bodies” underneath; there is a woman in a nurse’s uniform above the label “volunteer service”; and a woman can be seen working on an airplane, perhaps installing its propeller. This is a poster proclaiming the importance of the home front and the dignity and honor of the Black women fighting on it.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, NYPL, image id psnypl_scf_061.

Books Are Weapons – World War Two poster by NYC WPA War Services promoting knowledge about Black history and culture, the war's colonial entanglements in Africa, and the role of Black Americans in national defense. The books referenced were housed in the New York Public Library's renowned Schomburg Collection.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, NYPL, image id 5211531.

Bonds and justice will smash the Nazis, not bondage!

World War Two poster – The word "bonds" can work three ways here: the bonds or chains pictured here as broken, the bonds that unite us, and U.S. war bonds. The second of these offers the most powerful contrast to "bondage."

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, NYPL, image id psnypl_scf_065.

Thinking of a member of Orange Oaf's cast of terrible characters…

Don't Kill Our Wild Life – Department of the Interior, National Park Service – By Works Progress Administration – Federal Art Project NYC – [ca. 1936–40]

Via Library of Congress.

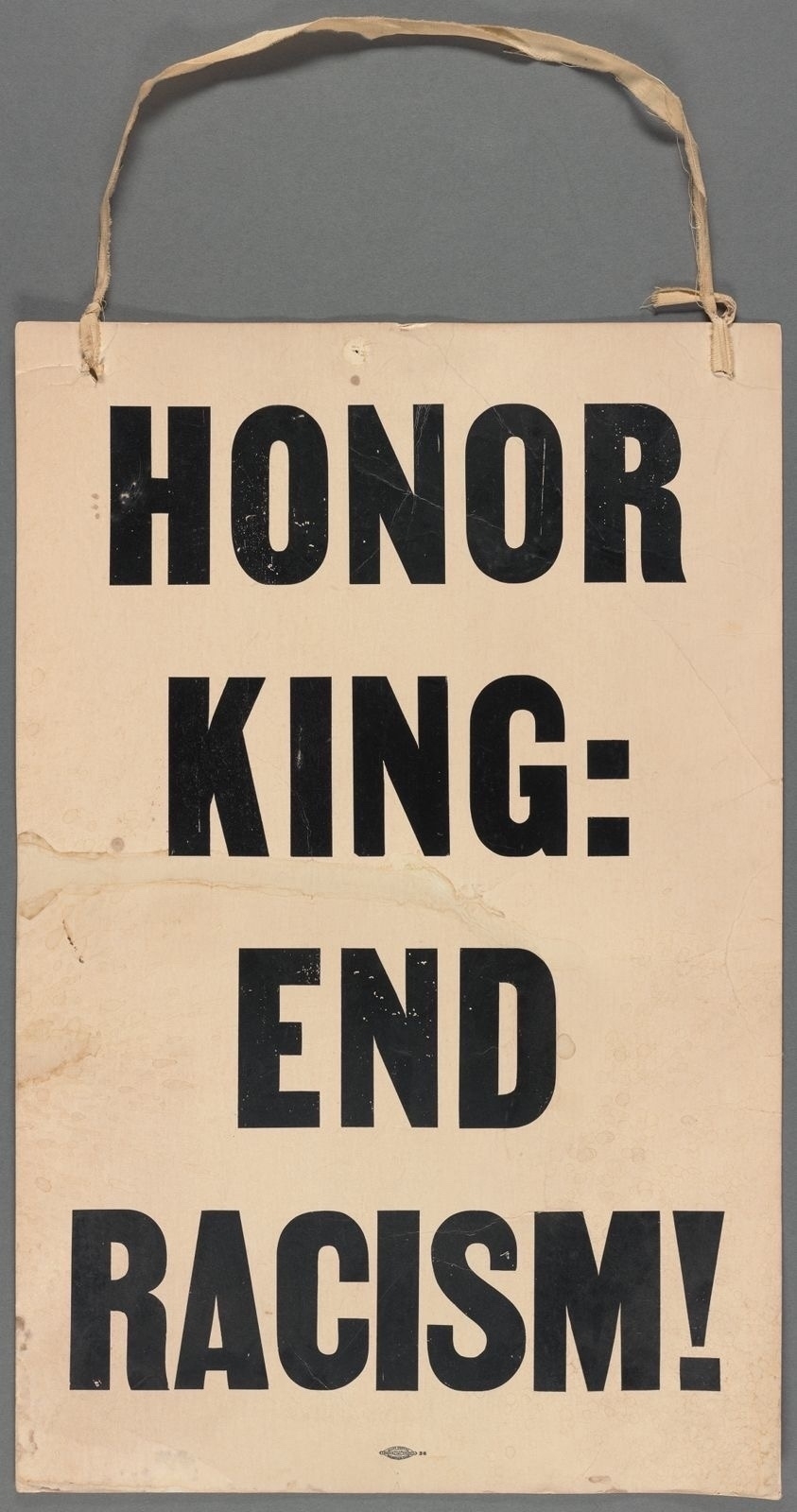

Now that I’m more than 20 years older than Martin Luther King, Jr., ever had a chance to become, his youth at the time of his murder is much clearer to me, much starker. It makes his achievements seem that much greater and his death all the more painful.

Pictured above: photos of two buttons and a poster from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, The New York Public Library, image IDs 57281864, 57281854, and 58250348.

Poster: Cartoon of the German and Italian dictators trying to cobble together what was left of their obscene project in 1945.

Source: Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015646607.

Poster from the Spanish Civil War, ca. 1936–39. The main text reads, “We charge the rebels as assassins! Innocent children and women die. Free men, repudiate all those who support fascism in the rearguard.” The text, bottom right, with the arrow pointing at the mother and child reads, “Here are the victims.” Note, too, the black and red triangle of the Anarchists in the lower right-hand corner.

Source of image and main text translation: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb5188576r. This page also offers historical context and analysis.

Iowa Art Project WPA poster for a Winter Sports Festival on Jan. 20, 1940, in Hubbard Park [Des Moines] and on Jan. 21 at Gilman Terrace [Sioux City], sponsored by the Jr. Chamber of Commerce and the Recreation Department. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/89715174/.

I watched “Passage to Marseille,” dir. Michael Curtiz (Warner Bros., 1944), this evening.

I forgot about the shocking scene in which Humphrey Bogart’s character machine-guns the surviving crew of the German plane he’d just downed at sea. The audience in 1944 was meant to sympathize with this act. After all, that crew had just tried to bomb the small civilian freighter. I don’t know if such a scene would have worked in a Hollywood film much earlier, but it did in 1944. Was this fictional atrocity an indication of American popular culture’s brutalization in World War II?

Movie poster image source: “Warner Bros. Pressbook” (1944), Internet Archive.

U.S. Government Caricature of Nazi Propaganda

This 1942 poster was designed to counter the effects of Nazi propaganda in the United States. It is fascinating in its own right, but parts of the text reveal startling similarities to Russian disinformation in our own time.

Accessibility: Description and full transcription of poster.

Two U.S. Public Health Service Posters Warning against Quacks, ca. 1936–41

Poster from 1919 Advocating American Citizenship

The notice in the bottom-right corner reads “Copyright 1919, The Stanley Service Co.” According to the Library of Congress Copyright Office’s Catalogue of Copyright Entries for that year, the company in question was the Stanley Industrial Educational Poster Service in Cleveland, Ohio. This provenance suggests to me that employers were being offered this messaging for their workers, even if the artist portrayed the immigrants as fresh arrivals.

Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/95507947/

DC Residents Still Have No Vote in Congress

For more than 25 years, I had no representation in Congress because I lived in DC. That’s changed because of my caregiving responsibilities, so it will be bittersweet on Tuesday when I cast a straight Democratic ballot in Conway, NH. Yes, I have representation now, but that doesn’t change anything for my wife, friends, and former colleagues and neighbors in DC. A territory in the United States with more than 700,000 residents,1 DC has more people than Vermont and Wyoming. That’s why its license plates read “Taxation without Representation.” Other DC PR work has included these 2006 posters.2

Rubbing DC residents' noses in it, representatives sent by the rest of the country interfere in the city’s local life.3 In particular, Republicans who don’t approve of local measures or have a social experiment in mind can interfere with local policies. I remember school vouchers and condoms for high school students. Democrats are not immune to such behavior either, however, as this 2023 tweet by President Biden demonstrates.4

I support D.C. Statehood and home-rule—but I don’t support some of the changes D.C. Council put forward over the Mayor’s objections—such as lowering penalties for carjackings.

If the Senate votes to overturn what D.C. Council did—I’ll sign it.

Workplace Safety Posters, ca. 1936–40

I am enjoying Depression-era workplace safety posters from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). They evoke a time when the power of government was effectively leveraged for good. If you live in the United States, there is a good chance you’ve encountered WPA building and infrastructure projects. One WPA program was the Federal Arts Project, which put artists to work. To get a feel for the diversity of programs this art supported, see the Library of Congress’s online collection.

Unfortunately, the WPA also built and helped staff internment camps for Americans of Japanese descent after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. This part of the story underlines the negative potential of government power when racism shapes policy.

Besides the four posters that follow this text, I include a photograph of an alley behind a row of houses with tiny back yards in Baltimore. If you look closely at this image from the Farm Security Administration, you can see a WPA poster attached to an open door in the bottom left-hand corner. It is captioned “Stop accidents before they stop you.” The building itself appears to be part of a factory of some kind because only a door and a single big wall with windows is visible, visually distinct from the opposite side of the alley, where all the little houses are.

These posters remind me of the ongoing importance of government for writing, publicizing, and enforcing workplace safety regulations. They connect past concerns about workplace conditions to countless reports of workplace injuries and sickness in our own time. They also link to family stories past and present, whether handed down or forgotten, whether taught or ignored in schools, workplaces, and union gatherings.

My grandmother’s father was killed in an avoidable industrial accident in 1917 when she was six years old. The lathe he operated in a Cleveland factory had no safety guard, and then his luck ran out. He left behind six children and their mother, the oldest of them able to work. The sudden loss of this man represented a trauma that no one talked about in my childhood, and I only learned the barebones details from my mother this past year.

I often wonder if and how such trauma is passed down in other families, and why its causes are silenced or not. My mind goes there because I imagine that millions of Americans—from across the political spectrum—come from families with such experiences, even if these were not handed down from the past. And I wonder what, if anything, knowledge about these many pasts might do to change their attitudes today.

This thought ties in with the employers and politicians who fight government regulations and workers' collective bargaining. They strive to steal workers' freedom and dignity, all in the name of their own freedom. Part of this effort benefits from or fosters processes of families and communities forgetting or diminishing the significance of the workplace struggles and traumas in their own pasts.

Fortunately, good governance and organized labor seem to be making a comeback.

World War I Poster: How to Act during an Air Raid

Air raids were a new danger in the Great War, and people within range of enemy aircraft needed to know what to do. The main caption of this related instructional poster reads, “How should I behave during an air raid?” Five captioned cartoons in the top row show what not to do. Below each of these is the recommended life-saving response.

The apparent repetition and contradiction in this anonymously produced poster suggest that the poster was less a product of foresight and more an ad hoc response to recent events or rumors.

Source: “Wie verhalte ich mich bei Fliegergefahr?,” poster from the Kriegsbilder exhibit of the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, https://ausstellungen.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/kriegsbilder/items/show/28. Physical object: Hessisches Landesarchiv. License: CC BY 4.0 Attribution.

Ringing in the New Year: Peace and War, Hope and Fear

Red Cross Poster with Christkind, circa 1917

"Christmas collection of the Bavarian Red Cross for our men in field gray" reads the caption of this Red Cross poster from Germany during the Great War. The angelic Christkind it features shines bright yellow in the dark Christmas night as she delivers parcels wrapped in field grey to men on the front. Stars twinkle above her, and there is snow underfoot. To her left is a sled heavy with more parcels, and to her right is a dependable, mustached soldier, pipe in mouth, a freshly delivered parcel in his hands.

A photograph taken in Louisville, Kentucky the same year, shows a similar effort by the American Red Cross: women preparing Christmas parcels for American soldiers.

Repository: Library of Congress.