Historical Images

- “Beware the cancer quack / A reputable physician does not promise a cure, demand advance payment, advertise” by Max Plattner, Works Progress Administration – Federal Art Project NYC, for the U.S. Public Health Service in cooperation with the American Society for the Control of Cancer, ca. 1936–38, via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518641/.

- “No home remedy or quack doctor ever cured syphilis or gonorrhea / See your doctor or local health office” by Leonard Karsakov for the United States Public Health Service, ca. 1941, via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/96502760/.

-

Caption from Catalogue of Official A.E.F. photographs taken by the Signal Corps, U.S.A., 1919. ↩︎

-

Photo by the United States Army Signal Corps, November 11, 1918, via Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017666571/. ↩︎

-

“Welcome to All!,” color lithograph, Puck April 28, 1880, pp. 130–31, Library of Congress, PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002719044/. A high-resolution TIFF file is available for closer scrutiny. ↩︎

-

Michael Alexander Kahn and Richard Samuel West, “What Fools these Mortals Be!": The Story of Puck (IDW Publishing, 2014) ↩︎

-

“The Unrestricted Dumping Ground,” via The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c146bf32-7fda-68d3-e040-e00a1806693f. This page includes a high resolution TIFF download option, which is what I used to examine the detail. ↩︎

- "Protect your hands! You work with them," poster (silkscreen) by Robert Muchley for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518513/.

- "Be careful near machinery," poster (woodblock) by Robert Lachenmann for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, ca. 1936–1940. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518717/.

- "Work with care," poster (woodcut) by Robert Muchley for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936 or 1937. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92517365/.

- "Failure here may mean death below – safety first," poster (woodcut) by Allan Nase for the Federal Art Project, WPA, Pennsylvania, 1936 or 1937. Repository: Library of Congress PPOC, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98518429/.

- "Backyards, Baltimore, Maryland," black and white photograph by Dick Sheldon for the Farm Security Administration, July 1938. Repository: The New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ba309cea-94b2-4288-e040-e00a18066c61

- “Get away from the window! Curiosity is death!” The sketch shows a terror- or awe-stricken family looking out, many mouths wide open. Instead of gawking, the poster commands readers, “Stand individually behind pillars!”

- “Never remain standing on an exposed road!” “Always seek cover!”

- “Don’t stand behind the door!” This is followed by more advice about strong pillars or load-bearing sections of the wall.

- “Panic is worse than an air raid!” Pictured are people hurrying down the stairs, one person holding a candle, another an oil lamp. Underfoot is a small child who has fallen down, and ahead of these residents is an old man with a cane, about to be trampled. Instead of panicking, the readers are told, “Don’t worry about an attack at night!” Pictured is a man under a duvet sleeping soundly.

- “Never stand in the middle of the room!” The picture below this final warning shows a domestic space in which a man in bare feet and a nightshirt has behaved correctly: He is standing in a corner, an empty bed nearby, but the middle of his floor has disappeared.

- Puck cartoon marking the new year in 1914. A young man (the New Year) in a smoking jacket and a vest labeled 1914 says to the old year, dressed as Uncle Sam, "Have something on me, old man! Whatll it be?" The choices are two whiskeys, one marked "hope" and the other "fear". They are in a well-furnished upper middle class salon with an overhead electric lamp lighting their faces. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011649657.

- Cartoon sketch by John T. McCutcheon titled "Is that the best he can wish us?," published in the Chicago Tribune on December 31, 1917. It portrays an old man, 1917, disappearing into the annals of history (literally pages, one marked "history") as he wishes a younger man with a globe for a head ("The World"), "Scrappy New Year!" The new year is dressed as a soldier and is weighed down by infantry kit as well as a few artillery tubes and merchant ships. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010717171/.

- Red, white, and blue New Year’s poster with Baby 1919 flanked by Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty. Behind them is a big red sun with the text, “World Peace with Liberty and Prosperity 1919.” Europe was still in turmoil and experiencing violence, but Americans had reason to be optimistic. Thus, this lithograph from United Cigars (logo at Liberty’s feet) seems apropos for the time. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652819/.

Japanese-American Internment as 'Evacuation' and 'Relocation'

These photos of Japanese-Americans and a few resident aliens on their way to internment for the duration of World War II are accompanied by captions that avoid the language of imprisonment or confinement. Instead of internment, there is talk of “evacuation” and the War Relocation Authority.

These pictures also suggest what a rupture the location of their internment would represent. It is hard to imagine these urbanites stepping out into the barely settled terrain they were headed to, even if an advanced party of men without dependents was sent out a few weeks in advance to prepare for the others' arrival.

"Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of the Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-American children waiting for a train to take them and their parents to Owens Valley." Photo taken in April 1942 by Russell Lee.

“Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of the Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-Americans and a few alien Japanese waiting for a train which will take them to Owens Valley.” Photo taken in April 1942 by Russell Lee.

“Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of Japanese-Americans from West coast areas under United States Army war emergency order. The Japanese referred to in this sign were an advance group going to Owens Valley for construction work.” Photo taken in April 1942 by Russell Lee.

“Manzanar, Calif. Apr. 1942. Construction beginning at the War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry, in Owens Valley. Mt. Whitney, loftiest peak in the United States, appears in the background.” Photo by Clem Albers.

Source: Library of Congress: Farm Security Administration / Office of War Information Photograph Collection, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017744879, …/2017744872, …/2017817916, and …/2021647198.

Two U.S. Public Health Service Posters Warning against Quacks, ca. 1936–41

Poster from 1919 Advocating American Citizenship

The notice in the bottom-right corner reads “Copyright 1919, The Stanley Service Co.” According to the Library of Congress Copyright Office’s Catalogue of Copyright Entries for that year, the company in question was the Stanley Industrial Educational Poster Service in Cleveland, Ohio. This provenance suggests to me that employers were being offered this messaging for their workers, even if the artist portrayed the immigrants as fresh arrivals.

Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/95507947/

@Infrogmation asked on Mastodon what Mussolini was wearing on his nose in an image I had reposted. I didn’t know, but now I do thanks to @Infrogmation: Il Duce got a bloody nose in an unsuccessful assassination attempt in 1926. Talk about history rhyming! 👀

Photo from the first Armistice Day in Paris

“When the news became generally known that the armistice had been signed, the crowd went wild . . ."1

“Paris. Impromptu parades took place in Paris on Armistice Day, November 11th, 1918. Here are American soldiers pushing their way through the great crowds at the Church of the Madeleine, Paris. They are forcing their way towards Place de la Concorde down Rue Royale."2

“Oakies” by Stuart Davis, ink and black crayon on paper, captioned “In a Florida Auto Camp: ‘Don’t cry baby, popper’ll sell the spare tire, and we’ll look for a new boom somwhere else’”, in New Masses, vol. 1 (May 1926), p. 6. Repository: Library of Congress.

Election Night Illumination, Flatiron Building, New York City, color postcard, N.Y. Sunday American & Journal (W. R. Hearst, 1904), Library of Congress.

“Watching the election returns—great crowds before the Times B’ld’g. and Astor Hotel, New York,” stereograph card by H.C. White Co., 1907, Library of Congress.

Broadcasting Election Results and Taking Opinion Polls in 1872

The illustrated British weekly The Graphic published these two fascinating images of U.S. election technologies in 1872. Explanations from the publication follow.

“The Electoral Magic Lantern” aka Broadcasting Results (top)

“Mammoth stereopticon”, at the corner of Broadway and Twenty-Second Street. “By means of a stereoscopic apparatus and magic lantern, the telegrams [of election results] are rapidly copied on a glass plate, and then put in the apparatus. Large crowds assemble till early in the morning, to watch the returns, which are shown on the wall of some building, covered with a large white sheet."–from source periodical.

“Taking Votes in a Railway Car” aka Polling Voter Intentions (bottom)

“It is a common thing to take votes in the railway carriages during election campaigns, though strictly speaking, it is not so much taking a vote as ascertaining approximately which candidate will have the best chance. Each passenger enters the name of his choice on a piece of paper, and a gentleman, generally a politician, takes his hat and collects the votes. Bets are offered and taken, and after the scrutiny animated discussions arise, each man endeavouring to persuade his opponents."–from source periodical.

Source: Wood engravings by Paul Frenzeny (artist) and Francis Sylvester Walker (delineator), The Graphic, November 30, 1872, via The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. (Higher resolutions available.)

"Susan B. Anthony to the women of today: 'Everything but the vote is still to be won'" by Nina Allender (1872–1957) for the Women's National Party, Equal Rights: Official Weekly Organ of the National Woman's Party, February 24, 1923, via Library of Congress.

'Welcome to All' (1880 Cartoon)

This Puck cartoon from 1880 portrayed immigration in positive terms.1 Uncle Sam stands at the entrance to a wooden “U.S. Ark of Refuge,” a U.S. flag to the side. The image offers a strong contrast to the ramparts Uncle Sam stands at in 1903 and behind in 1916. Beside him is a list of “free” things offered by “U.S.”

FREE EDUCATION

FREE LAND

FREE SPEECH

FREE BALLOT

FREE LUNCH.

U.S.

The meaning of “free” varies here. Sometimes it has to do with “liberty” (free speech and the secret ballot), and other times “no cost.” If public (“free”) education is an achievement some in our own time wish to destroy, its existence was bound up with both senses of “free.” No tuition was required, sure, but it was also a precondition for a free people and for making Americans. “Free land” in this list would have meant federal lands according to the terms of the various Homestead Acts. But “free lunch”? What was that about?

This last item was initially a head scratcher for me. I thought it might be a comment or joke about immigrant expectations, but it seems the saying “no such thing as a free lunch” only gained currency during the middle decades of the twentieth-century. In fact, American saloons were offering free lunches at the time of this cartoon, so there really was such a thing for those who liked their beer and whiskey. Given the loads of correspondence and rumors between Europe and the United States, this kind of knowledge would have filtered through, too.

Because saloons are the context of these lunches, it is tempting to gender these free lunches “masculine” and assume the existence of a social critique of intemperate immigrant men. The image, however, shows heterosexual couples in the prime of life, suggesting that such gendered moralizing was not part of the artist’s intention. Moreover, Puck had begun its life as a German-language publication in the previous decade, and the artist-publisher Joseph-Keppler had immigrated from Austria.2

Highlighting the list of attractions on the door is the metaphorically clear sky over the “ark.” Behind the migrants, to the east, are dark storm clouds with black carrion-seeking scavengers in them. The clouds themselves are monsters labeled “WAR” and “DISTRESS.” War entailed not only destruction but also mandatory military service of varying terms. Distress, in this context, probably meant economic distress. Europe was in the middle of a long depression, while it was continuing to experience great socio-economic changes in the course of its ongoing industrialization.

Adding more economic and political arguments to the mix, more liberty, a sign in the middle advertises more benefits to life in the United States:

NO OPPRESSIVE TAXES

NO EXPENSIVE KINGS

NO COMPULSORY MILITARY SERVICE

NO KNOUTS [OR] DUNGEONS.

The cartoon’s pairing of dark and light, of the prospects of distress or prosperity, represented what migration discourse in our own time refers to as push and pull factors. Beneath the cartoon is a quote from the N.Y. Statistical Review that highlights the cartoonist’s main interest: “We may safely say that the present influx of immigration to the United States is something unprecedented in our generation.” The detailed cartoon offered a context for this rise.

UPDATE: On Bluesky, @resonanteye.bsky.social reminded me of the Page Act of 1875, which excluded Chinese women. That made me think of the two single men at the end of the line in this cartoon because one of them appears to be Chinese. It is likely that this represented an acknowledgement of the Page Act. It also seems possible that the inclusion of this figure amounted to a critique of it. Here's our exchange—unfortunately, her settings require one to be logged in to see her posts.

Wealthy 'Criminally Insane' Playboy Posing with Captors (ca. 1913–14)

Sometimes the world loves a notorious, wealthy, narcissistic, sociopathic, murdering playboy sadist. This one was Harry K. Thaw, seen here posing in chummy fashion with Canadian police and immigration officers around the time of his escape from the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in New York. What a strange photo!

Credit: Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, ca. 1913–14, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017648770/.

Winslow Homer, 'Bell-Time' (1868)

I used to occasionally run across Winslow Homer’s wood engravings of the American Civil War, which were widely circulated in Harper’s Weekly, but this is the first work of his I’ve seen that deals with immigrant factory workers in the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts. Note the mix of genders and ages, including the presence of young children. This was not work that could feed a whole family. No matter the difficult pecuniary circumstances of his subjects, however, Homer portrayed them with dignity.

Credit: “Bell-Time” by Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, July 25,1868, via Smithsonian American Art Museum.

'The Unrestricted Dumping Ground' (1903 Cartoon)

This color cartoon by Louis Dalrymple appeared in Judge magazine in 1903.1 It linked immigration to national security by portraying Italian immigrants in ways that prefigured Trump’s despicable, racist rhetoric about “bad hombres” and pet-eaters in the present presidential race. The federal government, personified here as Uncle Sam, comes off as old and ineffectual.

At least, that’s what I see. Here: Old Uncle Sam stands at the ramparts of fortress America, bounded by the sea. The smoke from his pipe forms a wreath to his left. In that appears the late President William McKinley, assassinated in 1901 by the Polish-American anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Uncle Sam has an arm and hand around the flagpole and a cane in the other hand. Rats, monkeys, and other immigrating vermin emerge from the water, clamber up the rampart, and scurry away.

Some of the dehumanized immigrants are armed with a knife or pistol, and they wear a floppy, broad-brimmed hat or a bandana in anarchist red or the Italian tricolor. Their weapons and head apparel read “Socialist,” “Anarchist,” “Murderer,” “Assassination,” and “Mafia.” More inhuman riffraff falls from a garbage chute marked, “Direct from the slums of Europe daily.” There is also a cluster of regular gray rats in the harbor.

The message is clear. The immigrants, in this case Italians, are criminal, radical, or just socially undesirable. They are other, vermin, and their presence threatens the country.

Photo of “African American demonstrators outside the White House, with signs ‘We demand the right to vote, everywhere’ and signs protesting police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama” by Warren K. Leffler, March 12, 1965. Source: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014645538/.

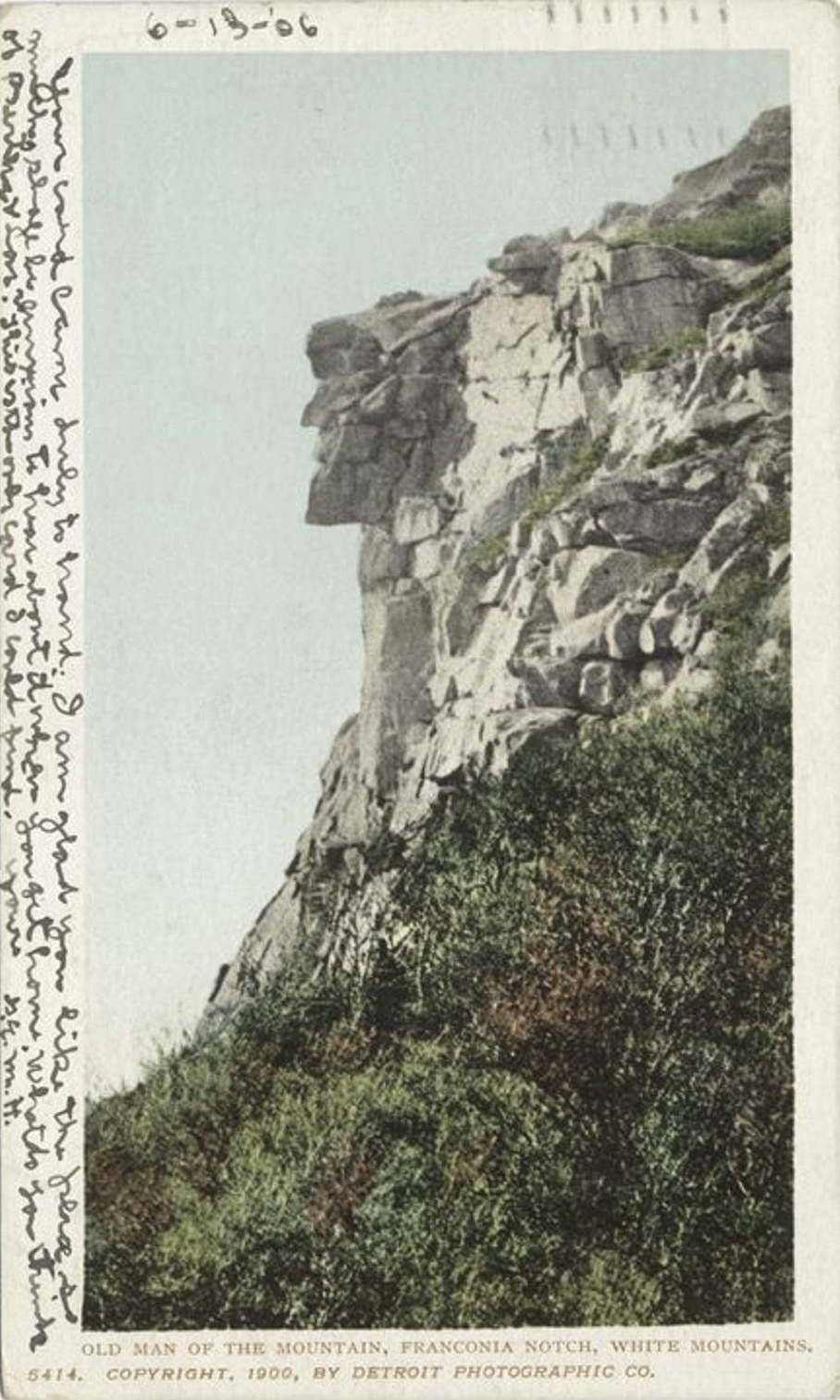

Old Man of the Mountain postcard written in 1906. The Old Man, located in Franconia Notch, collapsed in 2003, but he remains a symbol of the state.

Postcard by the Detroit Photographic Co. Digital image from The New York Public Library, Image ID 62116. To learn more, see the history, images, and links at Wikipedia.

"Two U.S. Navy sailors browsing library shelf labeled 'Negro Books'" – U.S. Navy Department, Office of Public Relations, ca. 1944-49.

To scrutinize the titles in this image, download a high resolution scan from the NYPL Digital Collections.

W. E. B. Dubois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903) is clearly visible. Also: Charles S. Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (1943) and Louis Adamic, The Native's Return (1934).

Repository: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/22e61340-6379-013b-2df1-0242ac110003.

Follow-up remarks: Revisiting Image of Two Back Sailors Browsing Books (Sept. 7, 2024)

Related post: Reading about Black Librarians and Knowledge Formation (June 19, 2024)

Workplace Safety Posters, ca. 1936–40

I am enjoying Depression-era workplace safety posters from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). They evoke a time when the power of government was effectively leveraged for good. If you live in the United States, there is a good chance you’ve encountered WPA building and infrastructure projects. One WPA program was the Federal Arts Project, which put artists to work. To get a feel for the diversity of programs this art supported, see the Library of Congress’s online collection.

Unfortunately, the WPA also built and helped staff internment camps for Americans of Japanese descent after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. This part of the story underlines the negative potential of government power when racism shapes policy.

Besides the four posters that follow this text, I include a photograph of an alley behind a row of houses with tiny back yards in Baltimore. If you look closely at this image from the Farm Security Administration, you can see a WPA poster attached to an open door in the bottom left-hand corner. It is captioned “Stop accidents before they stop you.” The building itself appears to be part of a factory of some kind because only a door and a single big wall with windows is visible, visually distinct from the opposite side of the alley, where all the little houses are.

These posters remind me of the ongoing importance of government for writing, publicizing, and enforcing workplace safety regulations. They connect past concerns about workplace conditions to countless reports of workplace injuries and sickness in our own time. They also link to family stories past and present, whether handed down or forgotten, whether taught or ignored in schools, workplaces, and union gatherings.

My grandmother’s father was killed in an avoidable industrial accident in 1917 when she was six years old. The lathe he operated in a Cleveland factory had no safety guard, and then his luck ran out. He left behind six children and their mother, the oldest of them able to work. The sudden loss of this man represented a trauma that no one talked about in my childhood, and I only learned the barebones details from my mother this past year.

I often wonder if and how such trauma is passed down in other families, and why its causes are silenced or not. My mind goes there because I imagine that millions of Americans—from across the political spectrum—come from families with such experiences, even if these were not handed down from the past. And I wonder what, if anything, knowledge about these many pasts might do to change their attitudes today.

This thought ties in with the employers and politicians who fight government regulations and workers' collective bargaining. They strive to steal workers' freedom and dignity, all in the name of their own freedom. Part of this effort benefits from or fosters processes of families and communities forgetting or diminishing the significance of the workplace struggles and traumas in their own pasts.

Fortunately, good governance and organized labor seem to be making a comeback.

World War I Poster: How to Act during an Air Raid

Air raids were a new danger in the Great War, and people within range of enemy aircraft needed to know what to do. The main caption of this related instructional poster reads, “How should I behave during an air raid?” Five captioned cartoons in the top row show what not to do. Below each of these is the recommended life-saving response.

The apparent repetition and contradiction in this anonymously produced poster suggest that the poster was less a product of foresight and more an ad hoc response to recent events or rumors.

Source: “Wie verhalte ich mich bei Fliegergefahr?,” poster from the Kriegsbilder exhibit of the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, https://ausstellungen.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/kriegsbilder/items/show/28. Physical object: Hessisches Landesarchiv. License: CC BY 4.0 Attribution.

Waging War with Factories

Production. B-17F heavy bomber. Working on the roof of a B-17F (Flying Fortress) bomber swung over on its side in the Boeing plant at Seattle. A turret will be mounted over the large circular opening. The Flying Fortress, a four-engine heavy bomber capable of flying at high altitudes, has performed with great credit in the South Pacific, over Germany and elsewhere.

– Andreas Feininger, December 1942, United States, Office of War Information, Library of Congress

The library has a large collection of photos showing the manufacture of B-17 bombers under the subject heading United States–Washington–King County–Seattle.