My wife is reading a crime story I got for Christmas and read over the holidays, Christian von Ditfurth, Mann ohne Makel. It’s sleuth, Josef Maria Stachelmann, is a historian of the Third Reich. Wonderful read, if you know German. Anyway, my wife asked me about the Hossbach Protocol that Stachelmann is supposed to give a talk about. My memory failed me, so I took the easy way out with Google. Bad idea.

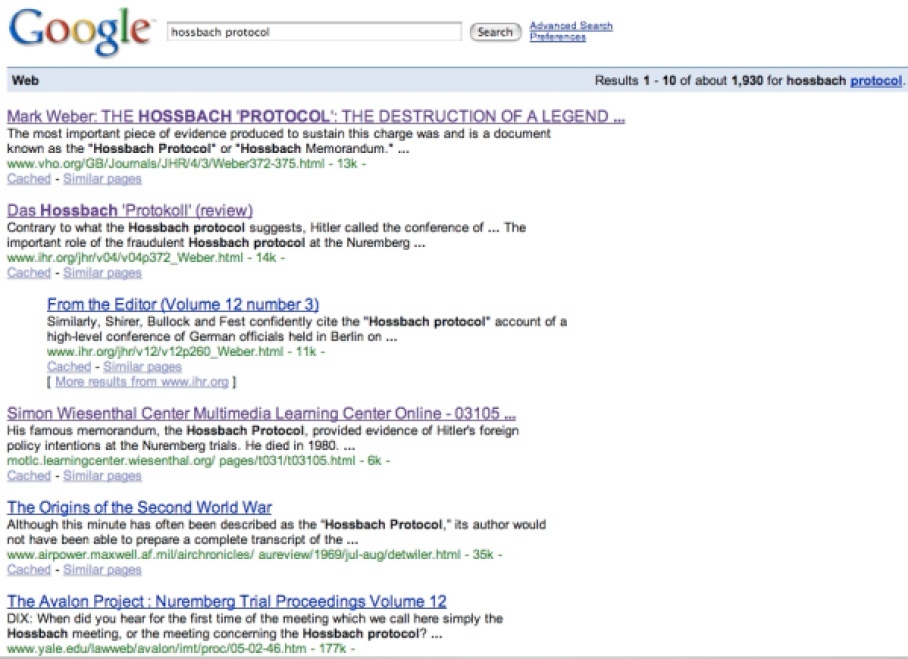

The first two hits on Google led to web sites that seek to appear legitimate, but which are in fact sites that deny the Holocaust and consider the Nuremberg Trial a travesty of justice. How did Google mess this up? Have some Nazi would-be academics learned search engine optimization (SEO)? Or was this blind luck? I’m not sure how Google’s search engine works, but the results here certainly point to the limitations of algorithms that rely on the syntactic relevance of a site. Also, while no one is linking to the articles about the Hossbach Protocol directly, there are many links to the main sites on which the articles appear. (You can determine who is linking to a site by typing link:www.name-of-site.com into the Google search box, unless the site is using the nofollow attribute in its links.) In other words, the sites appear to be popular and therefore relevant in Google’s eyes. In fact, Google has blessed both sites with respectable, if not overwhelming page ranks (PR). The first one Historical Revisionism, comes in at a PR 4, and the second one, Institute for Historical Review, at PR 5 on a scale of 0 to 10.

Now I could stop with this warning about the limitations of Google search results, but perhaps there is more to be learned here. Perhaps I should also issue a plea to historians to both learn SEO and write for general audiences on the web. Like it or not, Google is the first place many people turn for answers, and anyone seeking one on the Hossbach Protocol can be easily led astray. Actually, historians might not even need to learn SEO. Wikipedia already has a high page rank and its pages turn up regularly at or near the top of Google search results. Perhaps all that is needed is more and better Wikipedia articles. The Hossbach Protocol doesn’t show up in Wikipedia. If it had, the search results would have been different.

Wikipedia brings up another twist. Typically, when one uses one term in Wikipedia that is more commonly known by another, Wikipedia will at least offer alternative results. (It’s better than Google that way. Google can only offer spelling alternatives.) In this case, though, the more typical American name for this document did not show up in the search results. Only after I typed Hossbach Memorandum did I find what I was looking for. I then typed this term into Google and came up with much more satisfactory results. Only one of the right-wing links came up on the first page, and this time near the bottom.

This final result brings me back to Wikipedia and SEO. We need to enter all possible variations of terms in Wikipedia articles so that they show up in search results. (Sure, I should have entered “Hossbach Memorandum” right from the start, but I translated directly and that was that. As the first set of search results shows, others have done so too.) We also need to do the same thing with web articles and blog posts. It won’t do to leave the field open to the bad guys, simply because the world of SEO isn’t part of our training and does not make or break historical careers. I don’t know if Deborah Lipstadt does any SEO, but her three-year-old blog combats holocaust denial and has a PR 6. More established historians need to follow her example in their respective fields.

First published on this date on the now closed Clio and Me.